|

| Nancy Mitchnick, That is One Mean Mother Fucking Shark, 2012, oil on canvas, 36" x 53.5" (All images courtesy of the artist). |

One of the original members of the legendary Cass Corridor Group, Mitchnick settled in another of the region's noted bohemias, Hamtramck, a small ethnic enclave virtually surrounded by Detroit, which had been incorporated as a separate city in 1922 essentially as a tax haven for the Dodge Brothers Company, which for decades operated their main assembly plant nearby. The artist took a studio in the Russell Industrial Center, a mammoth seven-building complex designed by architect Albert Kahn in 1915 for the Murray Body Company, a supplier of stamped metal automotive components for manufacturers who lacked large-scale fabrication facilities, including Dodge, Hudson, Hupmobile, and Studebaker, and now home to artists studios and other creative enterprises.

Once Mitchnick arrived in the city and set up shop, however, she found that she was unable to develop the "Detroit Project" as the ideas simply wouldn't come. Instead, she began working on a series of "covers," i.e., works that reinterpret famous masterpieces that have influenced her development as artist and to which she returns in times when her creative batteries need recharging. Some 20 of these paintings were on view at the historic Scarab Club in Detroit this past fall in an exhibition titled "Time Travel."

In discussing the series, Mitchnick has confessed to not really knowing what to make of it. But it just so happens that at the time I was reading Alfred Gell's Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Clarendon: 1998), which offered some insight. A Reader in Anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, Gell died of cancer in 1997 at age 51, and he only published three books in his lifetime. Considered one of the most gifted anthropologists of his generation, Gell completed the full draft of Art and Agency shortly before his untimely death. He sought in this posthumous work to posit a theory of art that was, as the postmodernists have it, de-centered, that is, specifically extricated from Western aesthetic ideology. And I have to admit that for me it was a game changer.

Instead of looking at art (a problematic word in this context) as a form of expression, Gell asserts it as a form of doing, a nexus of complex intentionalities, not always conscious, that mediates social agency (in social science, the capacity to act). Not unlike Bruno Latour's concept of the actant in actor-network theory, agency in Gell's view may be situated in any number of places, not just the artist's intention. For example, the demands of religious ritual exert agency over the creator of sacred objects. More prosaically, a patron exerts agency over a portraitist, who is bound to execute a likeness in fulfilling a commission. Even the contemporary artist is in a very real sense subject to the agency of an artworld he or she must negotiate socially, economically, intellectually, and aesthetically. Working off of the thought of American pragmatist philosopher and coiner of the term "semiotics" Charles Sanders Peirce, Gell understands art as constituting the "abduction of agency," the trace by which agency can be inferred similarly to the way we infer fire by the presence of smoke.

The art nexus has four elementary nodes:

- First, is the index, which is the material thing that motivates abductive inferences, interpretation, and so on.

- Second, is the artist (or other originator) responsible for the existence and characteristics of the index.

- Third, is the recipient, those upon whom agency is exerted by the index or who exerts agency via the index.

- Fourth, is the prototype, which is what is represented in the index and which may or may not entail resemblance.

In relation to the prototype, the artist (in this case Mitchnick) is actually the recipient of agency (in the form of the impetus of the sources she reworks), and the index (each individual painting) is its material embodiment. Every artist, of the trained variety at least, studies the canon of previous creations (AKA art historical masterworks) and identifies those that inspire and/or influence him or her. The various paintings in "Time Travel" are indexes of prototypes Mitchnick encountered either in person or through printed sources. That Is One Mean Mother Fucking Shark, 2012, is based on John Singelton Copley's 1778 oil painting Watson and the Shark (itself likely influenced among other sources by Peter Paul Rubens's Jonah Thrown into the Sea, 1618), a version of which is in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Art. It is a painting Mitchnick has viewed countless times going back to her childhood.

|

| Detail: Las Meninas, for Olivia, 2011-2012, oil on canvas, 24" x 16". |

|

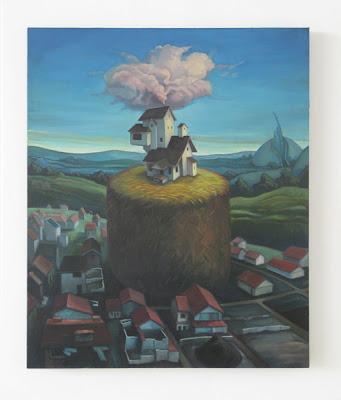

| Memory and Ruin, 2012, oil on canvas, 59" x 99". |

Memory and Ruin adds original details to the prototype, which none of the other paintings in the series does. (The typical conceit of the other works is to focus on a particular detail of the prototype and riff off that but not to really add anything new to it.) The work indexes the future past of the stalled series begun in anticipation of ending a self-imposed exile, precursors to the work that will be done when the "Detroit Project" is taken up again (which as of this writing the artist has begun to do). It also indexes the artist's personal history along with her creative one. All of them together constitute what phenomenologists term a "sedimentation," the physical record of experience evidenced through layers of space and time. Each of the sedimentary strata also indexes the various sorts of prototypes exerting agency over the artist's production. (As an aside, all artworks are essentially existential ruins, vestiges of the artist's agency in the moment of creation, which at the instant the brush touches the canvas begins to fade into memory.)

While "Time Travel" is in some respects a detour from the artist's trajectory, a retention that melds weak and strong prototypes in anticipation of the next chapter in the development of an oeuvre, it offers insight not only into Mitchnick's specific practice but artmaking in general. It is a most interesting case to consider, and it will be even more interesting to see what comes next.

|

| Detail of the artist's mother from Memory and Ruin. |